Drissa Goita has earned a reputation for punctuality and reliability among his colleagues.

By Stuart Russell

Drissa Goita has earned a reputation for punctuality and reliability among his colleagues. A civil servant in Mali’s Ministry for Solidarity and Humanitarian Action, he was selected as a finalist for Mali’s Integrity Idol program. His image and deeds were publicized through a national television and radio campaign, spreading his reputation across the country.

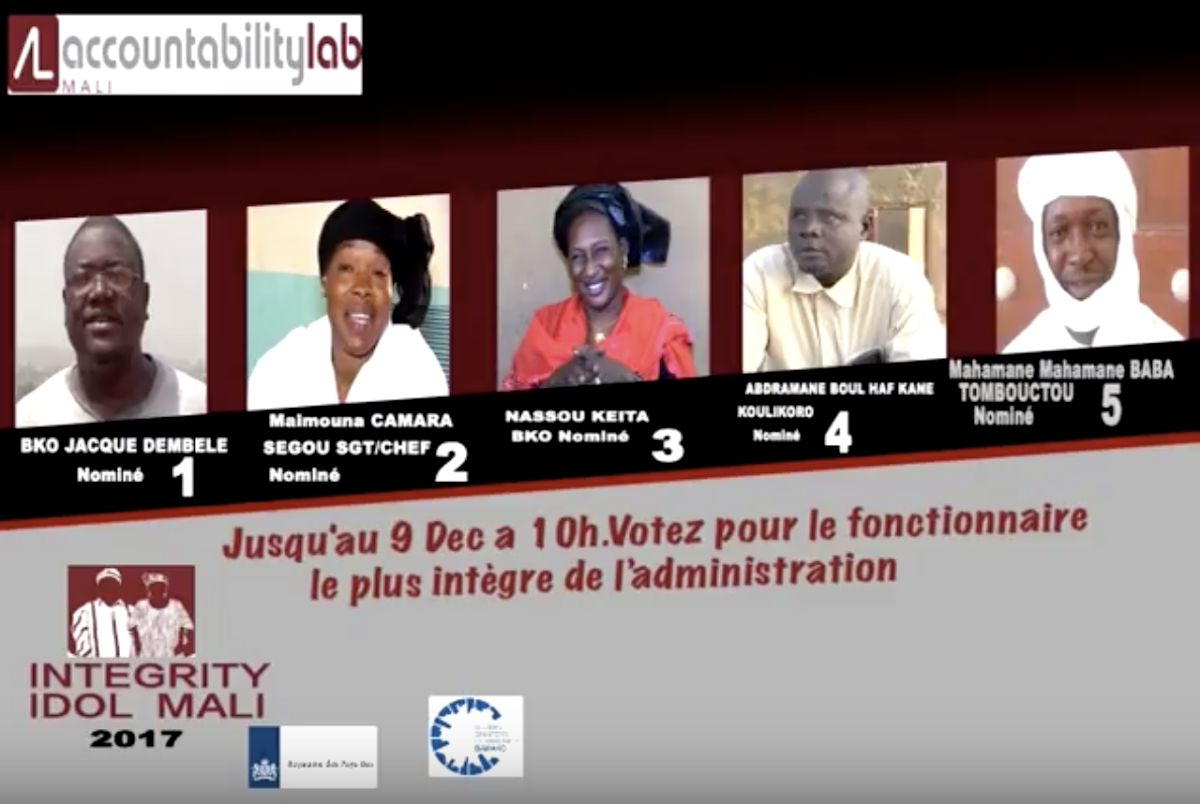

Integrity Idol – an Accountability Lab initiative – celebrates bureaucrats nominated for the integrity and hard work they demonstrate in their jobs. Each year in Mali, independent experts select five finalists from hundreds of these nominated civil servants. The stories and careers of these finalists are featured on nationally broadcast videos and radio spots. Rather than “shame” poorly performing civil servants, the objective is to “fame” effective ones with the hope of incentivizing better performance among individual bureaucrats and changing the public’s perception of the Malian bureaucracy more broadly. The conventional approach of shaming bureaucrats assumes that their superiors are able and willing to punish poorly performing employees. However, high-level bureaucrats and politicians may be corrupt themselves or may not even have the authority to sanction effectively.

In contexts where shaming is relatively unproductive, can media campaigns publicizing high-performers like Goita and incentivize civil servants to be more effective?

Research in political science and economics has explored how financial incentives, such as salary bonuses for attaining performance measures, can motivate civil servants. Though effective in some contexts, financial incentives are costly, difficult to administer, and can attract individuals driven by self-enrichment rather than a desire to serve the public good. Non-financial incentives, like the Integrity Idol “faming” treatment, are potential alternatives. With support from a MIT GOV/LAB seed grant, I spent three weeks in Bamako, Mali interviewing over twenty-five teachers, administrators, and other bureaucrats about their involvement in Integrity Idol. Through this scoping visit, I hoped to better understand how the finalists and their colleagues react to the publicity the program generates. I reflect below on some observations that came out of this preliminary trip. Two weeks in the field is only a start, and these ideas are not meant to be comprehensive or conclusive.

Almost every finalist started our conversation by describing the potency of the media campaign and the subsequent attention it brought to their work. (Here’s a spot from the 2017 campaign.) They received phone calls, texts, and in-person visits from friends and neighbors – and even strangers – wondering why they were selected for the program and what it meant for their career. Many finalists said that acquaintances in Europe and the United States congratulated them following their selection. One primary school teacher working in a rural community said, “When I was selected, it was a grand celebration. Practically the entire village was there to welcome me and accompany me from the town center to my home.”

Many civil servants found the public recognition encouraging. The rural primary school teacher, for instance, said that the selection “gave me a new spirit.” His selection motivated him to continue teaching in his remote community even though other teachers frequently requested transfers to avoid the difficulties of living in such an isolated area. Goita’s colleagues stated that, after he was selected, individuals in their agency started to emulate his punctuality. Instead of showing up late and leaving halfway through the day, employees came to work on time more frequently and stayed for the entire work day.

Other conversations, however, revealed differences in the effect of faming, especially across different government agencies. Superiors in some of the more hierarchical institutions like the military questioned the recognition and publicity their subordinates received. The superiors of one soldier selected as a finalist were suspicious of his motivations and transferred him to a more difficult post following his nomination. Another finalist working in the military was hesitant to participate in the program until she obtained written approval from the head of the Malian Army.

These conversations emphasized the importance of understanding the bureaucracies in which civil servants work and the incentives that these environments can create. Many Malians do not trust the government and, by extension, they don’t trust individual bureaucrats either. In an environment where suspicion is common, civil servants in the bureaucracy may not even trust each other. Superiors may worry that high-performing subordinates seek to take their place. Subordinates may fear disputing the status quo in their agency if working to change the current situation challenges the authority of their superiors. More generally, suspicion and jealousy may prevent colleagues within the same agency from cooperating effectively. In these circumstances, high-performing bureaucrats may face pressures from their colleagues and from their superiors to conform to the status quo.

While previous political science research has focused on trust between citizens and the state, my preliminary interviews in Mali highlighted the need to better understand trust – or the lack thereof – between individuals within the state. If civil servants do not trust one another, introducing external incentives may not work as one hopes. Of course, this preliminary research reflects only a handful of observations and just begins to scratch the surface of how to better understand the impact of Integrity Idol in Mali’s complex political system and bureaucracy. Understanding trust within bureaucracies may be the next step for understanding how incentives shape the performance of civil servants like Drissa Goita.

Stuart Russell is a first-year PhD student in the MIT Political Science Department. His research interests include bureaucracies, public goods, and social services in sub-Saharan Africa.